Skewed approach: Our drugs policy is undermining Peel’s principles of policing

(This article was originally published in Policing Insight on 18th February, 2019)

Police tactics may disrupt drug supplies, but they cause more crime and even contribute to the use of children as a go-between in county lines, undermining Peel’s principles, says former Detective Sergeant and Chair of LEAP UK Neil Woods who argues it’s time for drugs laws to be reformed.

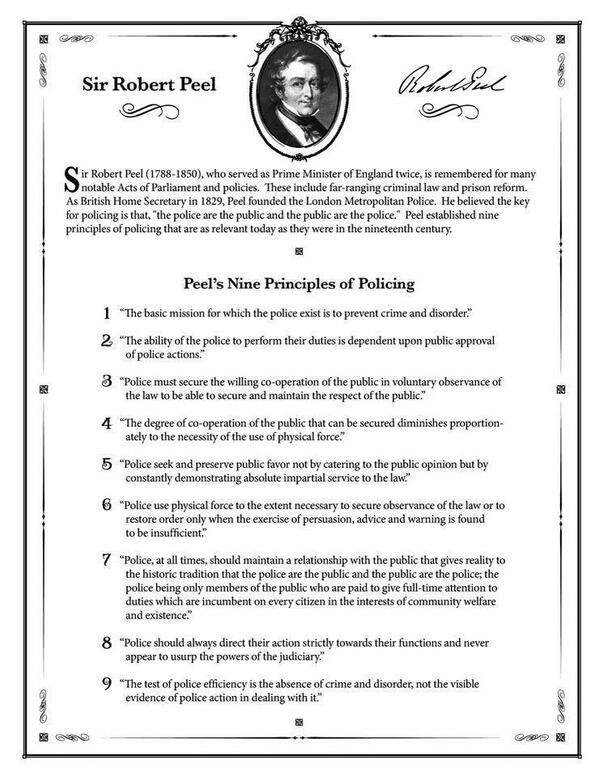

“The test of police efficiency is the absence of crime and disorder, not the visible evidence of police action in dealing with it.”

As the tools of media, and more recently social media, have developed so have the skills to use these for policing purposes. For a long time constabularies have had well qualified press officers and communications policies. It is one of the core responsibilities of any Chief Constable to maintain public confidence and in so doing any police service knows well to celebrate success, reassure the public, and to be seen to be ‘on the job’. The problem is that this has tacitly led to an institutional lack of honesty. If a recidivist burglar is arrested then rates of burglary are reduced; the demand for that crime has gone down because there are a limited number of people willing to take the risk and commit that crime in any given community. If a drug dealer is caught, however, then crime goes up. For example, if a cannabis dealer is caught with fifty 1 gram deals of cannabis, a Possession With Intent to Supply crime is recorded.

Common impact of drug crime

What is not recorded are the additional crimes that occur because someone else has filled the gap and is now supplying cannabis to customers. What we collectively understand from a policing perspective is that no one has gone without their drug of choice from that arrest. Evidence is clear from around the world that the common impact of many drug dealing arrests, at any level, actually causes violent crime to increase as the newly emerged business opportunity is fought over.

When the National Crime Agency (NCA) or Royal Navy create the latest ‘biggest haul ever’ headlines, what we may miss is context. The supply for heroin or cocaine is so abundant that the risk of such seizures is entirely taken by the international cartels. Payment is only made on successful delivery. So a seizure just means another shipment is sent.

There is some evidence that suggests the business losses for these cartels is less than high street shops write-off for the cost of shoplifting. The losses due to shoplifting is another drug policy failure that police see every day. There was a time in living memory in the UK where there was no association between drugs and crime at all, Organised Crime did not control the market and there was very little theft to pay for it.

I have conversation with a lot of people in the police and many, if not most, agree that the current situation is not working, and some even use terms such as “a mess”, and that reform is needed. Often though, police will say that it’s not their place to comment on the law or policy, it’s just their job to enforce it. This is absolutely a fair position. Except that the current practices of police are not so apolitical.

Whenever a newspaper story or social media post is used to celebrate the seizure of drugs or the arrest of a drug dealer, it is disingenuous, verging on hyperbolic, and this is damaging to community relations and clouds transparency. From Camden to Coventry, and everywhere else across the UK, and in fact the world, very few experienced police are deluded enough to believe that cannabis arrests, or cocaine seizures, have made the streets safer. Yet this is the message which is being echoed. To obfuscate the public like this is artificially prolonging a policy that needs urgent attention and reform. The cracks in international drug policy are showing, changes are happening, but not fast enough.

County lines

Police are very very good at catching drug dealers, but that’s part of the problem. Police never reduce the size of the market, but they do change the shape of it. The word ‘disrupt’ has become part of the police lexicon. That’s quite telling, because it declares an achievable aim that justifies the action against drug dealers. But someone tell me: if disruption is not reduction, why is it a good thing exactly? If we know that we are not reducing crime by our actions, and we know the risks of increased violence, why are we not honest about that? Are we not duty bound to be honest about such a revelation?

Consider the recent history of how police have changed the shape of the illicit drug markets. The exploitation of children for county lines drug dealing is tragically a result of police successes. It hasn’t just happened without cause, but it is a logical and strategic response to how drug dealers have been caught.

Children are a buffer zone between police and the dealers. They’re hard for Covert Human Intelligence Sources (CHIS) to gain intelligence from – easy to manipulate and disposable. What will be the policing response be to this growing tactic, an increased use of child informants? Surely we can all agree that this is not going to end well. Only by taking the markets away from Organised Crime can we protect children. Teenagers can get hold of cannabis or MDMA far easier than they can alcohol, because dealers don’t ask for identification. It is through these illicit markets that children are coming into contact with these criminals, they ostensibly become pathways to criminality.

Peel’s Principle number 9 is clearly being breached in an extreme manner. We are talking about policing tactic and actions which are likely to increase crime, but we give the impression to the public that it’s to make their communities safer. This is an incorrect reassurance, not allowing the evidence of failures in current policy to influence the voting public. The social movement for change is growing, and police figures need to be with it and not against it. The police service did not coin the phrase the ‘War On Drugs’, it was politicians who have repeatedly framed it in such terms. Well, if this current drug policy was an actual war, then misinformation is tantamount to propaganda.

I am far from alone in these observations. There is a growing international movement of law enforcement calling for drug law reform. I’m part of the Law Enforcement Action Partnership (LEAP), a UN accredited organisation, and in Britain we are known by our acronym LEAP UK, it was our organisation which led the British Medical Journal to form their own editorial stance in calling for the full reform and regulation of drugs.

Declaration

Appetite for reform is spreading across the world and last year we launched LEAP Scandinavia, to which the chairman of that particular international chapter is a serving officer who is head of serious crime investigations in Oslo. This year we will launch LEAP France, where there will also be serving police in the ranks. Sadly our brothers and sisters in LEAP Brazil have had to disband their group for fear of repercussions in the new government and regime, but this serves as a sobering reminder that in calling for reform we are championing basic human rights and safer communities.

Together with other law enforcement allies from around the world, most notably the Centre for Law Enforcement and Public Health (CLEPH), we have prepared a declaration from police calling for drug law reform. This document will be launched at the UN in Vienna in March at the Commission on Narcotic Drugs. We will be seeking signatures on this document from around the world over the next few months.

If you agree with us that this situation has to change then please sign up. The document link is here, if you agree then email your details to this address: info@cleph.com.au. The only details required are your name, where you are from, and your law enforcement position, past or present, and an email address is helpful too. Let’s be left with no doubt, our voices come from a place of service, and we can lead this dialogue in the much needed debate around drug policy reform.