Police’n Politics

When I was still a serving police officer, I would often find myself debating drug law reform with colleagues. Sometimes I would find others who were similarly disillusioned, others I would manage to convince of the Drug War’s true costs. Much of the time it was frustrating and pointless, as the belief structures of individuals prevented rational debate. Those that agreed, and those that disagreed generally had something in common; the feeling that their own beliefs did not matter. The general view is that Policy is for the law makers, not the law enforcers. So why are the views of the police now so relevant to the debate, and should the police have more involvement?

When I was still a serving police officer, I would often find myself debating drug law reform with colleagues. Sometimes I would find others who were similarly disillusioned, others I would manage to convince of the Drug War’s true costs. Much of the time it was frustrating and pointless, as the belief structures of individuals prevented rational debate. Those that agreed, and those that disagreed generally had something in common; the feeling that their own beliefs did not matter. The general view is that Policy is for the law makers, not the law enforcers. So why are the views of the police now so relevant to the debate, and should the police have more involvement?

The police officers who vehemently disagreed with me about drug policy reform can be divided into two groups. The first took the stance of the perfect optimist, declaring in a rather ‘gung-ho’ fashion that we could win the war on drugs, we could make the world drug-free if we tried a little harder. They also generally stated that we couldn’t legalise and regulate because that would mean that we had “given in”. This almost reduces the entirety of the reform debate down to the level of a football match. I don’t mean to criticise this view, these people of whom I speak believe that they are doing the right thing. Believe me, I went through a period of time in my days as a young man in the police completely trusting the law-making machine, seeing my role as fighting the good fight without question.

The second group of the unconvinced take a completely different view, which is one that deserves a little more study. This is the view that the drug gangster, the wholesale dealer, or the street pedlar, is first and foremost a criminal, and will always be so even if they weren’t dealing drugs. Within the national drug enforcement community there is a very influential individual who is a leading figure in his field; He was a Detective Sergeant in the Drugs Squad and is now one of the most knowledgeable experts involved. He is intelligent, charming and witty, and a very engaging speaker. I debated many times with him about reform, but I could never change his view. When I pointed out the benefits of taking the financial power of drugs supply away from gangsters he would reply “They won’t go away you know, they’ll always find another way to make money. There’ll be more armed robberies, more frauds, more everything.”

This view that criminals will always be criminals is a dangerous one, and from my experience working undercover I have found the opposite to be true. In inner city areas young people are tempted into the drug trade because it is the only thing that can offer any kind of advancement. A lack of social mobility pushes young men primarily into the world of the organised drug trade. This trade then shapes these young men, as they have to quickly learn the currency of fear. Ensuring that they are feared protects them from police informants and rival groups alike. One individual whom I observed stands out in my memory. A 16-17 year old in Leicester in 2003, who went by the name of “AB”. I observed him settling into his role as a budding gangster for about five months. Over that time it quite clearly shaped his personality as a young man, as he became more intimidating and more practised in how he needed to behave to survive and flourish. It is the illicit drug trade that creates the gangsters, not the other way around.

Making money selling drugs is easy; this is why there will be an endless supply of people willing to do it, as long as prohibition exists.

So for those police who realise that prohibition is a failure, should they speak out, or leave it to the law makers? I was very vocal with colleagues during my latter years as a police officer but I wasn’t publicly so. To be public is to enter into politics. Is this the police role? LEAP members in some countries are serving officers, and for that I commend their bravery. In Canada in particular there have been serving officers involved in court cases because their views on drug law reform have invited prejudice from their management and colleagues.

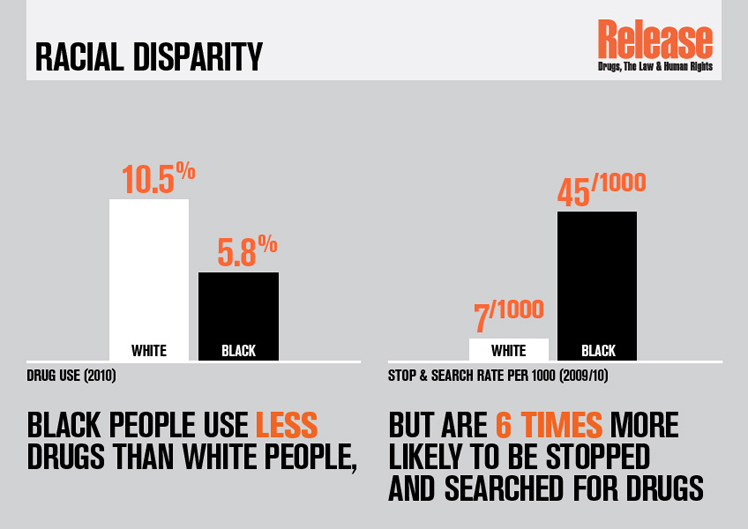

I have read recently in The Guardian1 that officers in Northamptonshire can have their right to Stop-Search someone revoked if they use it inappropriately. This is a move to try and build trust between public and police, however it appears to miss the most important issues with Stop and Search. Firstly, the majority of the public want to believe that a police officer abusing that power should be treated more harshly than merely being told they are no longer allowed to do it. Secondly, the problem with Stop-Search is that almost all searches are for drugs, and the tactic exposes endemic racism. In policing a law based on a moral judgement, by extension we ask the individual officer to make that judgement. Stop and Search has become the front line of a law that persecutes minorities and the poor. This is ruining public confidence in policing and causing long term damage to communities.

Below is a link to an extraordinary letter from the Derbyshire Police Crime Commissioner (PCC) Alan Charles to the Home Secretary2. It follows a conference in Derbyshire which listened to experts in the field of drugs. The letter urges a re-examination of our drug laws, and quotes the Derbyshire Chief Constable Mick Creedon as saying that successful policing of drugs is like cutting the head off a Hydra, as two more heads grow back.

The Hydra analogy is expanded on somewhat in a National Crime Agency study3 released on the 12th of August 2015 which suggests that urban Organised Crime Groups are taking over rural drug supplies, particularly when local enforcement measures leave a temporary gap in the market. Just three weeks ago Greater Manchester Police provided information that recent violence across the city occurred as a result of successful policing in the form of arresting high level gangsters4. However, the inevitable jostling for position causes violence every time without interrupting the supply of drugs.

The corruption of prohibition is constantly expanding. Gangsters get away with murder, and the communities in which they roam are oppressed by criminals and police alike. Police officers can see that the last thing a problematic heroin user needs is a spell in prison, and Chief Constables can see their budgets being eaten by endeavours that only cause harm. Gradually across the world it is those who are in the front line in this War on Drugs which are voicing the need to declare peace. So for this issue we are entering the world of politics, because the majority of establishment politicians are ignoring the evidence of the need for change. Or maybe you have to see the evidence at first hand to believe it.

The latest speaker for LEAP UK, Suzanne Sharkey thinks it is time for as many police to be involved in the debate as possible:

“Police on the streets see the harms. It’s not just the pointlessness of incarcerating people for drugs, it’s the damage to families left behind. The relationship between police and the communities they’re supposed to serve is damaged. Of course you can take the view that the police are there just to follow orders but a police officer is much more than that, we can’t keep the blinkers on any more.”

3 http://www.nationalcrimeagency.gov.uk/news/678-urban-drug-gangs-target-coastal-communities

It is really a sad to see the oldest democracy in the world act so irrationally, to stubbornly stick to a failed policy which causes so much harm in society.

Worse still to pretend that the laws are there to protect individuals from harm in the first place.

The problem here is the public debate is futile because the governments stance is based on lies.The reasons they continue to enforce these policies and cause misery here and aboard are political. Nothing to do with harms.

Another great article, Neil, thank you.

I tend to agree with the “Criminals will remain criminals” argument, but only actually apply it to those at the top of most criminal enterprises. Of course they will look to other forms of profit, but the vast majority of the individuals involved further down the chain are opportunists or victims themselves and would not. Anyway you look at it, harm from all angles including this one would be significantly, indeed largely, reduced by the cessation of the costly, damaging, compassionless, evidence-less prohibition.