Policing Drugs in a Racist Society

I think it is unfair to label British police as inherently racist. Our police are no more racist than the rest of UK society.

As a police officer I would have been extremely offended to be labelled with the socially divisive ‘racist’ moniker. My colleagues past and present would all similarly be upset at an accusation that their work was anything but impartial. However, by seeing the situation in simple binary terms we are not truly seeing anything. The evidence, depressingly, is all around us and is regularly exposed in the media. We have a collective unconscious bias in the UK that is exhibited in a deeply racist society.

It should not be a surprise that we have such endemic prejudice in every part of public life. We used to be a slave trading nation and generations have held with patriotic fervour that we are simply the best. The domination of the British Empire is remembered fondly and we are very sure of who was superior in its expansion. These echoes from our history are not just harmless nostalgia. They continue to play out today in tangible data. There are regularly reported biases in most professions, particularly for the best jobs in those professions. This is true in everything from catering to big business. It is true in academia and, of course, it is equally true with the police.

A recent report for the Guardian shows how racial bias in the criminal justice system (CJS) is felt by the UK black, Asian, and minority ethnic population (BAME). The findings are stark. Where prejudice plays out in the CJS, it has an acute effect on those on the receiving end of it. Criminal records can ruin lives. In the case of a BAME individual, it can reinforce the barriers to success for this generation and the generation to follow. The Lammy review in 2017 made it clear that BAME individuals are sentenced to prison more often and for longer terms than white people.

We need to understand the impact of drug policy on this whole situation. Drug laws have always been about racism. Overt, clear, fully conscious racism. Opium was banned in the USA because of prejudice against Chinese immigrants. Cannabis was banned to target Mexican immigrants, and was renamed Marijuana as part of that process. Cocaine was only banned once southern black people were perceived to be using it; just one more aspect of the Jim Crow laws.

In more recent history John Ehrlichman, former adviser to Richard Nixon, explained what the President’s ‘war on drugs’ was really all about – “The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people. You understand what I’m saying. We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.”

It is no accident that the Brixton riots here at home happened ten years after the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 (MoDA) was passed. An aggressive foreign policy from the USA led to worldwide prohibition, and so when the UK dutifully fell into line with the MoDA, police were given a new mandate and a war chest of powers to enact it. But drug laws are not really about drugs. They are about behaviour. More specifically the behaviour of ‘other’ people. In 1971 police suddenly had to decide who these other people were. For our book Drug Wars, we interviewed people from both sides of the Brixton riots and it is clear that tensions were stoked in the ten years leading up to the event by police searching for drugs, particularly cannabis. When we spoke to former undercover cop and TV personality, Peter Bleksley, he openly acknowledged he wasn’t racist before he joined the police, but after he was posted to the Met in south London he became a “racist thug”. He makes it clear that almost every search he carried out was for drugs and almost every search was of a black person.

The racism of the USA’s political classes has been exported through the process of global drug policy. Our British police were well and truly stitched up with drug prohibition, given an impossible task based on no evidence. They were asked to police a moral judgement, restricting personal liberty of individuals they didn’t understand. The action of creating prohibition precipitated a rise in organised crime and the widespread corruption we see today but the effect on BAME communities is still taking shape. Drug laws created far more interaction between police and community and it is clear they have damaged vital links with those communities.

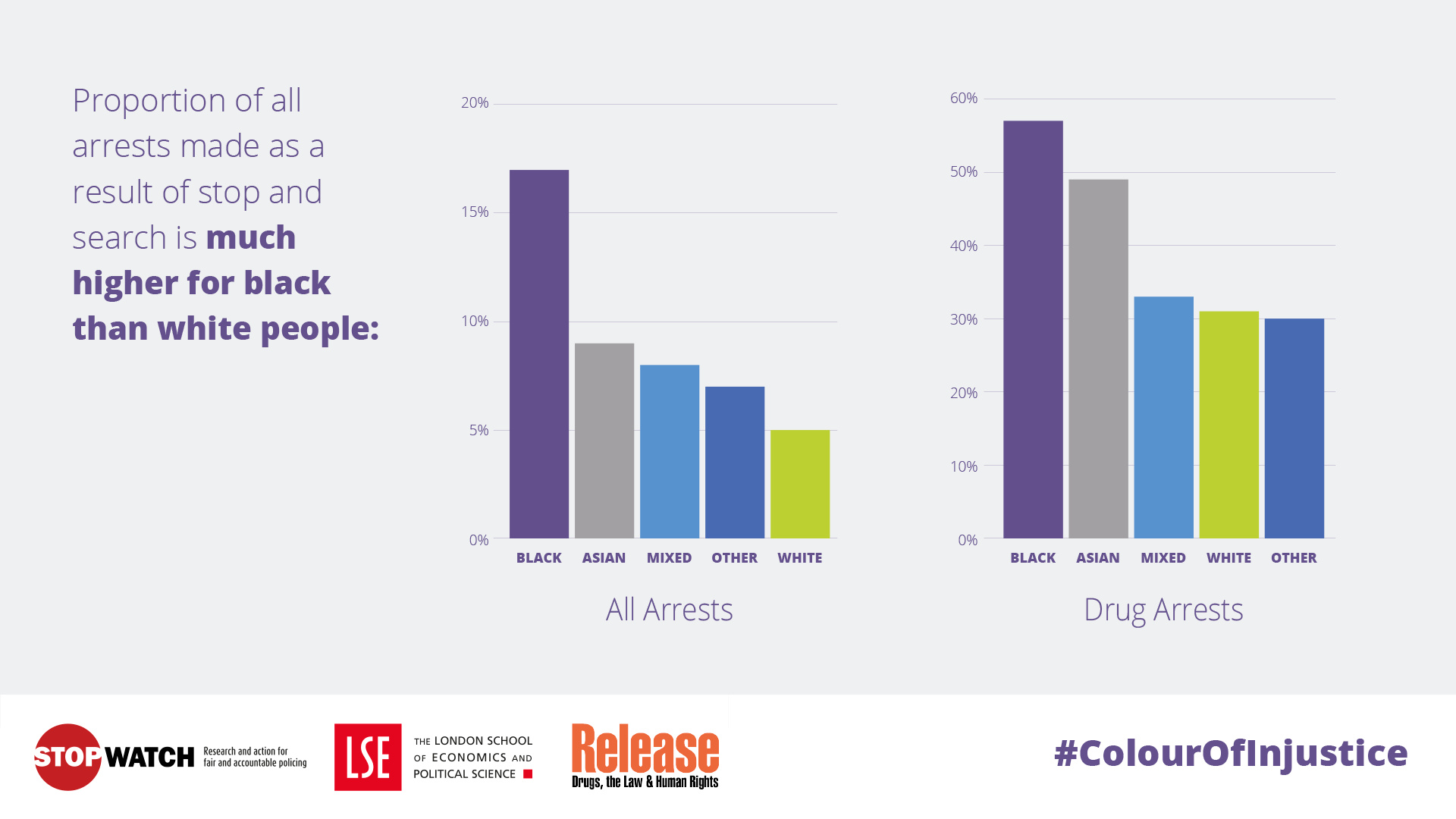

When Release, the drug policy reform and legal advice organisation, published their 2018 The Colour of Injustice report, they were subject to widespread criticism from defensive police voices. This is understandable. Police officers do not feel that they behave in a racist manner as they go about their duties in the service of the community.

If you use government estimates of the number of UK cannabis users, it works out at around 1 in 22 adults are consumers. Theoretically, if a constable patrols a street, every seventh property will house a cannabis consumer. Of course many communities will have a greater concentration of consumers. That is a significant section of our society for the police service to be at odds with.

60% of police stop and searches are for drugs. Black people are 8 times more likely to be stop searched for drugs than white people, despite evidence that they use drugs less. They are more likely to be charged once caught with drugs, and they will be sentenced more heavily once in the court. Note, I am not just blaming the police here. The whole criminal justice system is weighted against minorities, and even more so for drug related offences.

Organised Crime Groups (OCGs) target children who have been excluded from schooling to recruit to ‘county lines’ drug dealing networks. Researchers found that black children are three times more likely to be excluded from school than white children. Are black kids really more difficult to deal with than their troublesome white equivalents? I don’t believe so. It is clear to me that we have in these figures another indication of our nation’s structural racism. This is not the fault of the police – the education system is beyond their influence – but it has huge implications for policing. From the classroom to the court room there is a social disaster taking shape. It makes me shudder in horror that gangsters are picking on black kids because the system does.

The fact is that police are no more racist than the rest of society but what are we to do about the situation? There are many reasons to reform our drug laws but, for me, the growing impact on racial justice is the most urgent. The impact of current policy on the next generation does not bear thinking about. If we want to protect our children from organised crime and the racism of society we have to regulate the drugs market. There are obvious reforms we can implement immediately. Prescribe heroin to problematic users. Rescue them from the exploitation of OCGs and reduce the demand for county lines dealing. Regulate the cannabis market for adult use; good regulation will protect our children and remove the primary method of recruiting young people from the drug gangs’ arsenal. Only then can we begin the process of healing and increase cooperation between police and marginalised communities. The negative conversation dogging stop and search tactics will become very different indeed and we can begin to go back to policing by consent. For all racial groups.

Excellent article, Neil.

I agree that county lines are a massive problem facing our society. My hunch is that the dark net is a big part of this: tech-savvy inner-city kids witness the money to be made from peddling class A drugs, but realise that to do so in their own neighbourhood would probably spark a turf war. There is an exponential rise in the use / proliferation of both in recent years. Possible correlation?

The remedy, in my opinion, lies on the “demand” side, rather than chucking more and more at enforcing the supply side.

The intervention initiative being trialled in Maidenhead is most welcome, and I’m sure that it will be a resounding success.

Do try and avoid these awful euphemisms such as ‘policing drugs’ – the whole debate is full of dehumanising rhetoric and back to front legal gibberish (eg ‘illegal’ drugs).